Over the last two weeks I’ve attended a couple of workshops hosted by NESTA, the Teach First Innovation Unit and Brightside. The workshops have bought together people from various organisations that provide some sort of one to one support, either tuition, mentoring or coaching.

The aim is to discuss these three areas and see if there is enough shared common ground that we are able to give some general guidelines to best practice in one to one intervention.

As I promised in my first post, this blog is very much going to be me thinking aloud, so here are some of the ideas that I came away with from those discussions. I don’t promise that there is necessarily a through line between them all!

1. Tuition and Mentoring are defined by their goals, coaching by its method.

There is a well defined method to coaching that is particularly favoured in business. This involves open questioning with the aim of helping the recipient find their own answer to the problem they are trying to solve. The coach is not there to give answers, the idea is that the recipient should be able to find those answers.

Coaching can applied to different goals, but it is popular in business as a personal development tool. It has a well defined methodology.

Tuition and Mentoring on the other hand do not have well defined methodologies. There are things you can say about good tuition in general, but what a good tutorial looks like might vary hugely depending on the academic subject being taught and the age or ability of the student. Similarly there appear to be several ways of mentoring, although I have to admit my ignorance about this in detail.

However, tuition and mentoring are easily definable in terms of their goals. Tuition is one to one support aimed at addressing an academic need. Mentoring is one to one support aimed at addressing a personal development need.

2. A spectrum of directedness?

I’m sure I could eventually come up with a better term than that, but some members of the first workshop talked about the three kinds of one to one intervention existing on a spectrum. Coaching would give the least direction to the recipient, tuition the most, with mentoring existing somewhere in the middle.

This is interesting, because its definitely wrong. Sometimes a tutor will have to be very directive (to solve trigonometry problems you need to follow these steps), sometimes totally undirective (here are some problems with triangles. See if you can solve them). Indeed the hallmark of a good tutor would be the ability to judge how much direction the recipient needs. In some tutorials the tutor might in fact be playing a role very similar to that of a coach.

I can’t be as certain about mentoring but I suspect something similar might be true.

It might be fair to say that tuition is likely to be more directed purely in terms of setting your end goal, but not in how you get.

3. Engagement isn’t fun and fun isn’t the aim.

The nearest thing to an argument (actually a very friendly discussion) was on the desirability of fun. Some delegates talked about the need for recipients of one to one intervention to enjoy the experience. Some even used the word fun.

Unsurprisingly, I disagreed. I have no idea if this applies elsewhere, but notions of fun and enjoyability have been overemphasized in education. So much so that the word ‘engagement’ has been misinterpreted as ‘fun’ in some circles. Taken too far this can lead to educators mistaking themselves for entertainers which can definitely be a mistake.

I’m not claiming that recipients should hate the experience, far from it. What matters is not a sense of enjoyment but a sense of fulfilment. A sense that this intervention is useful to me, that it’s what I need and also (in tuition at least) that I’m having to work hard and push into knowledge that I’m currently not secure on.

4. How do you tell someone they’re disadvantaged?

Many of these charitable organisations are working with recipients who are socially disadvantaged in some way, most of them children or young people. So how do you let them know why they’ve been selected to take part in your programme without making them feel stigmatised?

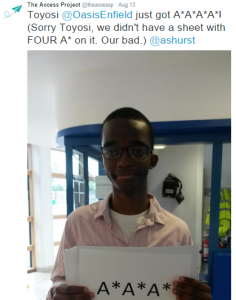

I don’t know the answer to that, but I do know that at the Access Project we have the luxury of working with older children. That means that, while I’d be very unlikely to use the word ‘disadvantaged’, I can start an assembly by saying ‘do you think it’s right that how rich someone’s parents are should be a deciding factor in where they go to university?’. Working with older students means you can have a conversation about fairness. You can discuss the advantages that money buys some and show young people that the Access Project is a means to replicate some of those advantages. You don’t need this because there’s anything wrong with you, you need it because others have an unfair advantage.

In summary

I know this a list of ideas with little structure. Sorry. Like I said, thinking aloud. It’s been really interesting to discuss one to one intervention with others and consider different approaches to coaching, mentoring and tuition. It’s also fascinating to see how many organisations there are working in this space, making the world better.